Date Range: November 16 – November 22

Hours Spent:

20 hours

- 5 hours on lectures and notes Professor Leonard – Calculus 2 Lecture 9.5: Showing Convergence With the Alternating Series Test, Finding Error of Sums

- Professor Leonard – Calculus 2 Lecture 9.6: Absolute Convergence, Ratio Test and Root Test For Series

- 15 hours on exercises (Thomas 13th ed, 10.5 questions 1 – 25, 10.6 1 – 27 & 49 – 56)

Summary:

This blog entry is a little lengthier than normal as it’ll be covering two different sections. That’s because Professor Leonard lectured on Alternating Series first, but the textbook covered Absolute Convergence, Ratio Tests, and Root Tests for Series before Alternating Series. As sections build on those preceding them, I ended up watching two lectures, and then completing exercises for the corresponding two sections. Bear with me.

Alternating Series

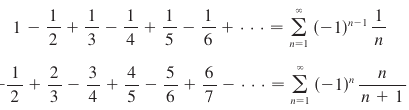

Up until now, we’ve looked at series with all positive terms. Alternating series are series whose terms alternate between positive and negative, like this:

Like with the other series, what we focus on here is determining convergence or divergence. In order to confirm convergence, we must know that it tapers down to zero. In other words, it must be decreasing and have a limit of 0. With that in mind, the Alternating Series Test checks if the limit is 0 and if the series is decreasing. Checking the limit is easy peasy, and checking that the series is decreasing (negative) can be as simple as noticing the obvious (like that denominator grows faster than the numerator as n increases), observing sequential terms, or taking the derivative of the series as f’(x) and checking that it’s negative. But, then it’s never as simple as it seems.

Absolute Convergence

After practicing with alternating series, we know how to work with both positive terms and those that flip back and forth, we turn our attention to series whose terms can switch between positive and negative in an irregular fashion. This leads us to look for if a series is absolutely convergent – that is its absolute value is convergent. We find that not all convergent alternating series are absolutely convergent (we call those that aren’t conditionally convergent), but all absolutely convergent alternating series are convergent. To check for absolute convergence, we dive into our grabbag of Calc tools, and learn two more to help us…

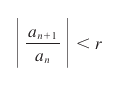

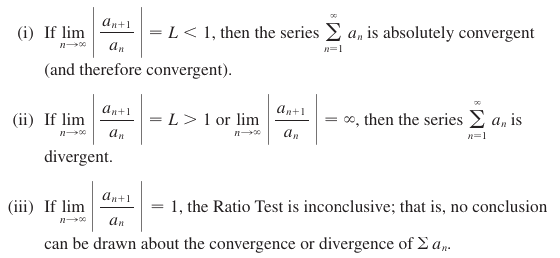

Ratio Test

Ratio tests are a way of comparing our series with a convergent geometric series. We look for a limit that is less than 1 (as geometric series |r| < 1 converge). We set up a ratio test thus:

Upon evaluating our ratio test,

If we can confirm convergence or divergence, we have an answer. If our test is inconclusive, we move on to test it another way. That might be…

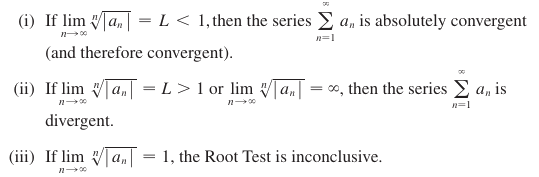

Root Test

Root tests are particularly useful for evaluating series with nth powers. Similar to a ratio test,

Root tests are particularly useful for evaluating series with nth powers. Similar to a ratio test,

So with some razzle dazzle, we remove away some pesky n’s and look for limits. Limits, limits, and more limits. These will get the job done for their task, as tools are designed to do.

Personal Observations:

- These two sections really challenged me

- Each test on its own makes good sense, no cryptic operations

- I had difficulty identifying what to use when – obviously some tests work better than others on certain problems

- I’ll admit that many times I’d try a test and think I found convergence or divergence, conditional convergence or absolute convergence, then check and find my conclusion was incorrect and that the author had used a different means of checking the series for convergence

- Throw in some log’s, partial fractions, trig equations, mix them all up and increase your complexity

- Like with integration techniques, there are so many different tools for working with series – how am I going to memorize them well enough to draw on them in the future?

- Like with the rest of Calc 2, pattern recognition is key

Reflections:

There is no substitute for practice, which is to say there is no substitute for failing, identifying why the failure happened, and trying again. Failure happens much more frequently than success. Success therefore contains much failure. Failure is the flour to the Success Cake. I feel frustrated when I work on a problem, flip back to the solutions to see I’ve not gotten the problem correct, but I let it go quickly. I feel it, see it, and let it push me on to practice more. Sometimes I’m just not in the right state of mind, so it’s best to put it down and come back later. It feels good to write about it, as it somehow makes sense of the process a little better.