I should have posted weeks ago. My host blocked my IP address, as apparently I’ve been located in a region flagged for fraudulent activity. Consequently, anyone using Telkomsel as an internet provider (Indonesia’s largest) in the Yogyakarta region (4.5 million people) would be blocked from accessing their website. I was advised by my website host to contact Telkmosel to sort it out. I would likely have a better return on my time by praying to the Norse gods for a solution as petitioning Telkomsel, so I left it alone. Yes, I probably could have circumvented the problem with some VPN, but my workload is such that I sideline the blog post until now — weeks later. I apologize for the truancy, teacher. But I really did study my Trigonometric Substitution, see…

—————————————————————————————————————————————

Trigonometric substitution is the next manifestation in a sequence of integration tools for integrals that previous tools couldn’t crack. Having made it this far, there’s nothing confusing about it. In fact, once seen, it becomes almost self-evident.

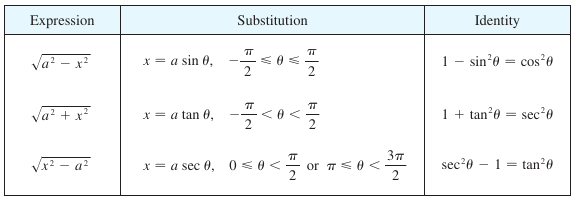

It’s built on the back of Pythagorean Theorem and the trigonometric identities that stem from it – specifically, sine, tangent, and secant. It’s all glued together with good old fashioned algebra and Calc 1 integration techniques. Basically, the rules are thus:

Professor Leonard does a superb job at teaching this. We start by drawing out the triangle (always draw out the triangle) and assigning a, x, and the square root of the two in their respective places on the triangle. With these in place, the rest if more of the same, which can range from a walk-in-the-park integration, to more involved calculations using multiple integration tools and tedious algebra.

Trigonometric Substitution is awesome because, like so much else in math, it originated from pattern recognition. Some bright mathematician saw, intuited, was graced by providence, or however their creative process took place, and they connected the dots. This is how a triangle comes together, this is how their sides interact, and we can apply those rules to helping us figure out tricky integrals.

Little did Euclid or Hipparchus of Nicaea know that the patterns that they recognized would then be drawn upon to identify new patterns, and thus form the brick and mortar of the next step in the stairway to the sky of understanding. Each new step I take up this stairway, the more amazed I am by how it all ties together, almost seamlessly, spurring on my awareness, curiosity, and urge to climb higher.